Effective temperature

The effective temperature of a body such as a star or planet is the temperature of a black body that would emit the same total amount of electromagnetic radiation.[1] Effective temperature is often used as an estimate of a body's temperature when the body's emissivity curve (as a function of wavelength) is not known.

When the star's or planet's net emissivity in the relevant wavelength band is less than unity (less that that of a black body), the actual temperature of the body will be higher than the effective temperature. The net emissivity may be low due to surface or atmospheric properties, including greenhouse effect.

Contents |

Star

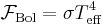

The effective temperature of a star is the temperature of a black body with the same luminosity per surface area ( ) as the star and is defined according to the Stefan–Boltzmann law

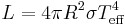

) as the star and is defined according to the Stefan–Boltzmann law  . Notice that the total (bolometric) luminosity of a star is then

. Notice that the total (bolometric) luminosity of a star is then  , where

, where  is the stellar radius.[2] The definition of the stellar radius is obviously not straightforward. More rigorously the effective temperature corresponds to the temperature at the radius that is defined by the Rosseland optical depth.[3][4] The effective temperature and the bolometric luminosity are the two fundamental physical parameters needed to place a star on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. Both effective temperature and bolometric luminosity actually depend on the chemical composition of a star.

is the stellar radius.[2] The definition of the stellar radius is obviously not straightforward. More rigorously the effective temperature corresponds to the temperature at the radius that is defined by the Rosseland optical depth.[3][4] The effective temperature and the bolometric luminosity are the two fundamental physical parameters needed to place a star on the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram. Both effective temperature and bolometric luminosity actually depend on the chemical composition of a star.

The effective temperature of our Sun is around 5780 kelvins (K).[5][6] Stars actually have a temperature gradient, going from their central core up to the atmosphere. The "core temperature" of the sun—the temperature at the centre of the sun where nuclear reactions take place—is estimated to be 15 000 000 K.

The color index of a star indicates its temperature from the very cool—by stellar standards, that is—red M stars that radiate heavily in the infrared to the very blue O stars that radiate largely in the ultraviolet. The effective temperature of a star indicates the amount of heat that the star radiates per unit of surface area. From the warmest surfaces to the coolest is the sequence of star types known as O, B, A, F, G, K, and M.

A red star could be a tiny red dwarf, a star of feeble energy production and a small surface or a bloated giant or even supergiant star such as Antares or Betelgeuse, either of which generates far greater energy but passes it through a surface so large that the star radiates little per unit of surface area. A star near the middle of the spectrum, such as the modest Sun or the giant Capella radiates more heat per unit of surface area than the feeble red dwarf stars or the bloated supergiants, but much less than such a white or blue star as Vega or Rigel.

Planet

The effective temperature of a planet can be calculated by equating the power received by the planet with the power emitted by a blackbody of temperature T.

Take the case of a planet at a distance D from the star, of luminosity L.

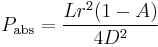

Assuming the star radiates isotropically and that the planet is a long way from the star, the power absorbed by the planet is given by treating the planet as a disc of radius r, which intercepts some of the power which is spread over the surface of a sphere of radius D. We also allow the planet to reflect some of the incoming radiation by incorporating a parameter called the albedo. An albedo of 1 means that all the radiation is reflected, an albedo of 0 means all of it is absorbed. The expression for absorbed power is then:

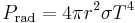

The next assumption we can make is that the entire planet is at the same temperature T, and that the planet radiates as a blackbody. The Stefan–Boltzmann law gives an expression for the power radiated by the planet:

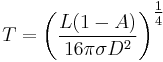

Equating these two expressions and rearranging gives an expression for the effective temperature:

Note that the planet's radius has cancelled out of the final expression.

The effective temperature for Jupiter from this calculation is 112 K and 51 Pegasi b (Bellerophon) is 1258 K. A better estimate of effective temperature for some planets, such as Jupiter, would need to include the internal heating as a power input. The actual temperature depends on albedo and atmosphere effects. The actual temperature from spectroscopic analysis for HD 209458 b (Osiris) is 1130 K, but the effective temperature is 1359 K. The internal heating within Jupiter raises the effective temperature to about 152 K.

See also

References

- ^ Archie E. Roy, David Clarke (2003). Astronomy. CRC Press. ISBN 9780750309172. http://books.google.com/?id=v2S6XV8dsIAC&pg=PA216&dq=%22effective+temperature%22+%22black+body%22+radiates+same.

- ^ Tayler, Roger John (1994). The Stars: Their Structure and Evolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 16. ISBN 0521458854.

- ^ Böhm-Vitense, Erika. Introduction to Stellar Astrophysics, Volume 3, Stellar structure and evolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 14.

- ^ Baschek (June 1991). "The parameters R and Teff in stellar models and observations". Astronomy and Astrophysics 246 (2): 374–382. Bibcode 1991A&A...246..374B.

- ^ "Section 14: Geophysics, Astronomy, and Acousticse". Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (88 ed.). CRC Press. http://www.scenta.co.uk/tcaep/nonxml/science/constant/details/effectivetempofsun.htm.

- ^ Jones, Barrie William (2004). Life in the Solar System and Beyond. Springer. p. 7. ISBN 1852331011. http://books.google.com/?id=MmsWioMDiN8C&pg=PA7&dq=%22effective+temperature+of+the+sun%22.

External links

- Effective temperature scale for solar type stars

- Surface Temperature of Planets

- Planet temperature calculator

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||